Originally published on 06/01/2020, and updated 21/09/2023

We often need to get information from people through forms. When we create forms, we have a responsibility to ensure they're crafted with inclusion and respect at the front of our minds.

For some people, something as simple as filling in a form can be a frustrating, demeaning experience. Sometimes something as small as a poorly-designed form field can serve as a reminder of their feeling of invalidation, exclusion or otherness.

In tech, there are "edge cases". But there are no such thing as edge case people.

For years, it's been part of my job to decide how to design forms. We've often needed to ask about gender. I've done a fair amount of research into how to write respectful, ethical forms and have been helped by invaluable conversations, feedback and ideas from others. Today, I'm sharing what I've learned.

The Golden Rule

What are we using the information for? Would not collecting it cause a problem? Will people feel comfortable answering?

If we ask ourselves why we're requesting a particular piece of information from someone, and nobody can answer, it's probably a good sign we shouldn't be asking at all.

In some parts of the world, it can be illegal to do so – more on this later.

This thought process also helps us explain to our user why we're asking. If we can give a good explanation, they'll likely be happier to give that information.

"If you don't need to know, don't ask."

When we ask unecessarily, at best, we ask for someone's time and labour in completing the question; at worst, our question is invasive or offensive. Not to mention that longer forms have worse completion rates.

So, we need to be mindful of how much information we ask for.

But there are plenty of good reasons to be asking about gender.

These might include...

- understanding demographic diversity

- tailoring user experiences or services

- addressing gaps in representation

- fostering a more inclusive environment

- many more!

When we ask, we need to do it thoughtfully, and ensure our users understand our reason for asking.

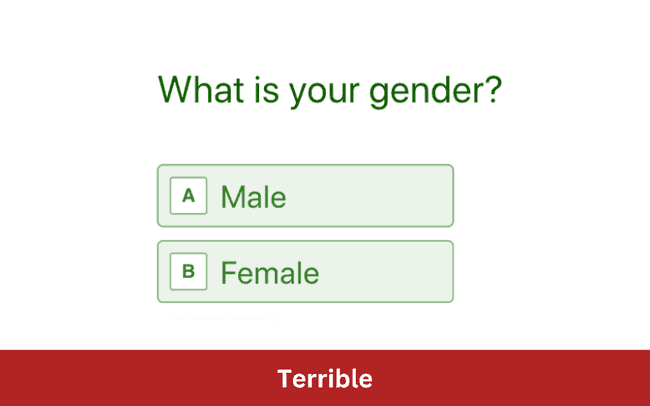

Building our form: the worst case

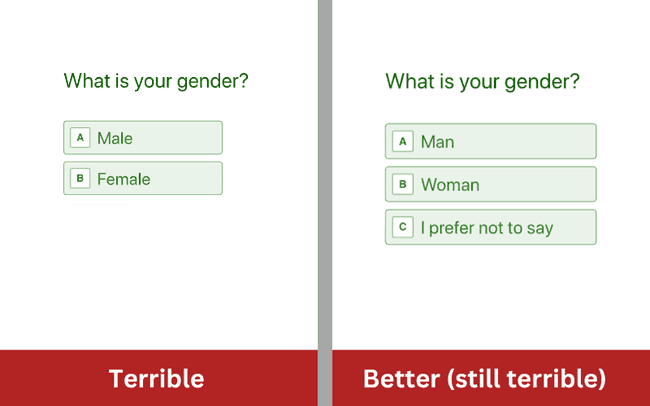

Let's look at the worst case, and use it as a starting point.

It's not good enough to simply ask people to select "male" or "female" in forms. If we need the information, we need to be far more thoughtful and considerate about how we ask about gender.

There are all kinds of ways we can improve this form. Let's visit them one by one.

Sex or gender?

Usually, it's not someone's sex we want to know about. Unless we're writing a medical form, we're likely more interested in gender. The UK Government recommends asking about gender, not sex, in most cases.

Sex is more about physical biology (though even asking about sex is complex), while gender is more about personal experience. And this is what really matters when we're trying to understand things like who uses our products, or diversity in our workplace.

For some people, the sex they were assigned at birth doesn't fit with their gender identity.

We usually care about the way people experience the world (gender), not biological sex.

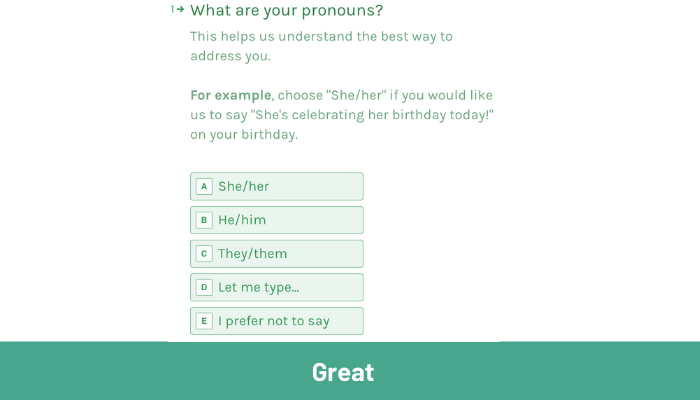

Do we just need to know pronouns?

If the reason we want to know somebody's gender is to know how to refer to them, what we're actually looking for are their pronouns.

Stonewall has a great introductory guide on pronouns.

We shouldn't assume that we know somebody's pronouns from their gender. For example, a non-binary person might use "she/her" pronouns.

Explain why you're asking and provide an example – not everyone will be familiar. You could try asking "How should we address you?"

Making it optional

We should always give people a clear option not to give an answer.

It should be possible to submit the form without answering a question like this. But that's not all – it should be obvious that we welcome people to not give an answer, so we should include this as an option – for example, "I prefer not to say".

We mustn't force people to give us sensitive information about themselves.

When we do this, not only can it cause stress and harm, we also risk excluding people who don't want to answer from using our service.

Often, people decide whether to give this information based on the context, so we should generally allow people to decide based on whether they feel comfortable doing so.

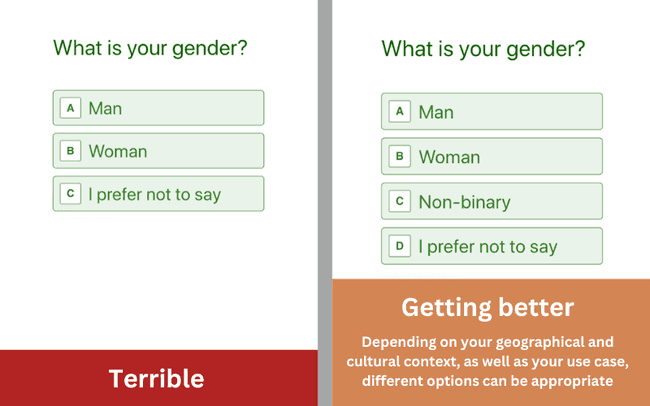

Different genders

Firstly, we usually associate "male" and "female" with sex, while we associate "man" and "woman" with gender for adults. So let's reflect that in our form.

"Man" and "woman" are by no means the only genders.

Gender is a matter of experience, and it is not a binary.

This is a really complex topic which deserves much more treatment than I can give it here. We'll cover some nuances as we go, and I will flag some resources along the way.

The reality of gender does not fit nicely into our idea of what forms should be like.

Some other gender-related terms are non-binary, intersex, transgender, agender, Two-Spirit, genderqueer or gender non-conforming (GNC) – there are many more, some are umbrella terms, and there are complex relationships between them. Not everyone chooses a name for their gender (or agender) identity at all.

Here's a helpful list of gender-related terms from Stonewall.

We certainly don't want to try and list every gender (or agender) identity. The form would simply be both confusing and inevitably incomplete.

The best practice here is to be vigilant about two things when considering what to include:

First, include reasonably common gender identities which match our geographical or cultural context.

Second, consider identities that might be relevant within the context within which we are asking.

If you're interested in learning more about this gender, sex and sexuality, I recommend this nuanced and thoughtful book by Morgan Lev Edward Holleb.

Additional contexts to gender identity

Some gender-related terms don't necessarily (though sometimes!) indicate a gender identity, and are often considered as additional context about gender identity rather than being one.

Some examples:

- Cisgender – Cisgender people are people whose gender identity match, and sit comfortably, with the sex they were assigned at birth

- Transgender – Transgender people are people whose gender identity don't match, or sit comfortably with, the sex they were assigned at birth

- Intersex – Intersex people have bodies – including organs, chromosomes, hormones and more – which differ from the societal assumptions associated with "male" and "female"

For example, somebody might be a transgender man, and might indicate they are a man and are transgender, or indeed, have transgender history. This might not always be the case. Cisgender people often find it intuitive that they wouldn't select "cisgender" and "woman" on a form. Some transgender people think about this in a parallel way.

It isn't usually necessary to include these when we ask about gender – but we should offer a way for people to mention them. More on this in the next two sections.

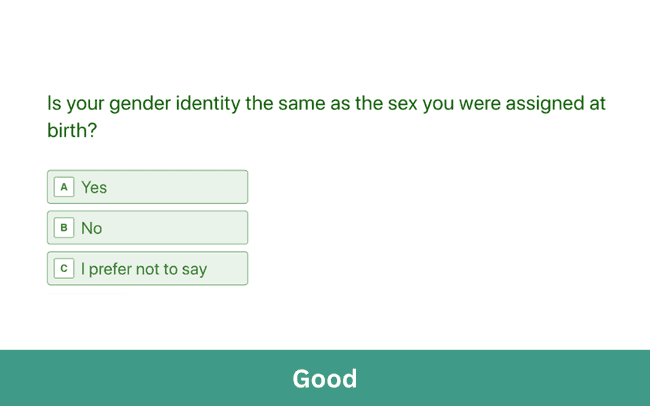

Asking about transgender identity, history or transition status

It's not considered good practice to add "transgender" – or variants – in your main question about gender.

If we were to have this as an option, we force trans people to choose between being a man, woman or other identity, and being transgender (and also might feel a bit strange to choose only transgender, because it might be considered more of a process than a gender category).

Adding "transgender man" and "transgender woman" won't solve this – this is microaggressive and harmful as it implies their status as a man or woman isn't valid. Transgender people also can have other gender identities.

If we need to ask, it's good practice to ask a separate question about transgender status.

Stonewall suggests "Is your gender identity the same as the sex you were assigned at birth?"

This phrasing avoids the assumption that people who have transitioned think of themselves as "transgender"or "having transgender history".

Asking this question offers separate but inclusive way to collect data on both gender identity and transgender and transition status, respecting the complexity of these aspects of identity.

You may not need to ask this question.

Depending on your use case and how importance granularity about transgender status is, the best place to offer the opportunity for people to mention this might simply be as part of an open field. Let's look at this next.

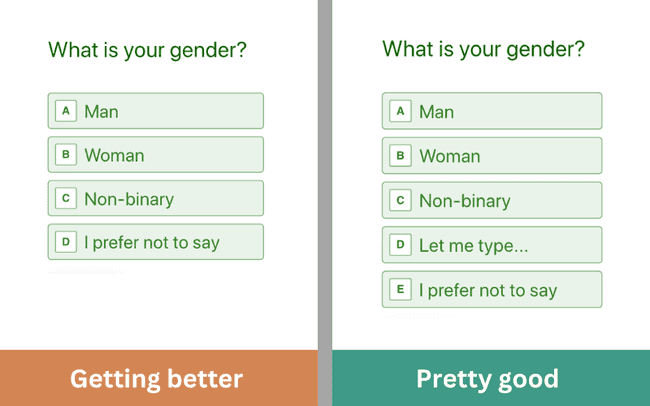

Let people type

Having an open field where people can type is often a good way of allowing our users to freely express their identity in their own terms, giving them agency and recognition.

This is particularly important for less commonly known or culturally specific identities.

If you're not asking a separate question about transition or transgender identity, this is where people will have the opportunity to add this information if they want to.

Avoid using the word "Other" as the typing option – firstly, it's not obvious it'll lead to the chance to type, but it's also not nice to feel as though you are an afterthought.

A note on identifying as

We don't need to say "identify as a...". This challenges people's status – for example, saying a trans man "identifies as a man" challenges their status as a man. Would we say that to a cis (assigned male at birth) man?

Challenge the status quo

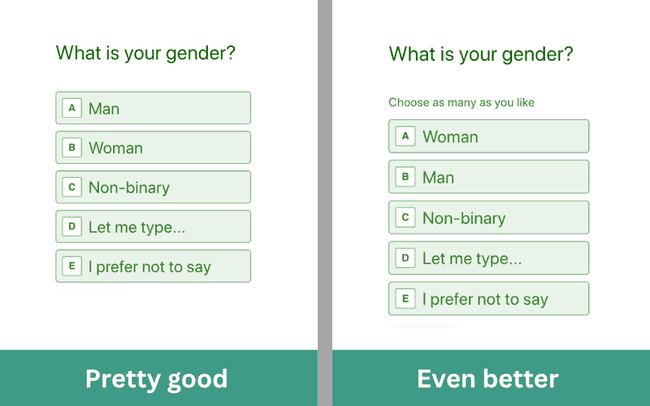

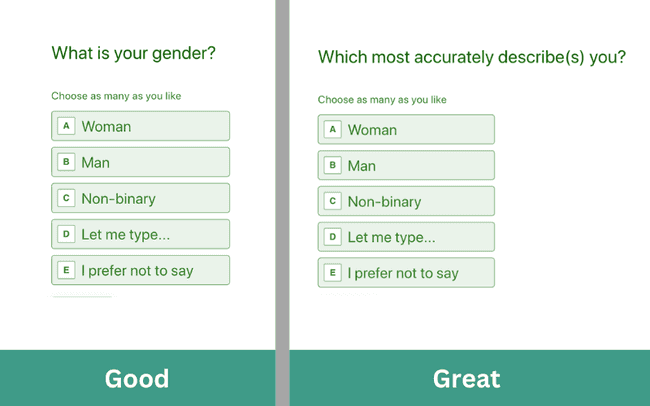

Since the vast majority of forms on the internet place men first in lists of options, why not do our bit for balancing things up and – perhaps – challenge people to recognise their own bias?

Selecting more than one option

Users should be able to multi-select.

In general, it's entirely possible to have multiple gender identities – or indeed, to want to select one option and still want to type more detail.

Not everyone has a gender

Some people don't have a gender. This is also known as agender identity, which is an umbrella term. To perfect the question, let's make one simple final change, and avoid making the question about having gender.

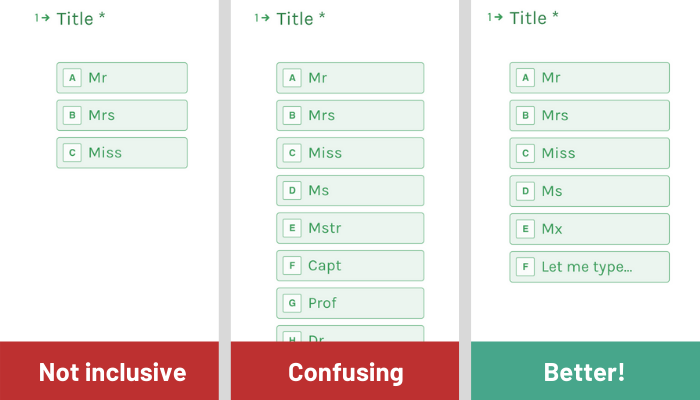

Asking for titles

Most businesses these days won't need people's titles. If we're not sure why we're asking, there's probably no need to. It's a weirdly antiquated practice, and often just an (unhelpful[]) proxy for marketing departments to get to the bottom of their customers' genders.

But if we do have a need, we need to consider including a gender-neutral option, and the option to type. Mx (pronounced "mix") is an accepted gender-neutral option to include.

By the way, here's a great blog on this topic from Zuko.

A note on data privacy

Collecting gender information involves significant data privacy considerations – both ethical and legal.

Best practice starts with informed consent: users should know why their gender data is being collected and how it will be used. Security must be a first priority. Data security breaches for this kind of information are treated extremely seriously in data privacy regulations around the world, including the European/UK GDPR and California's CCPA.

Both require clear, lawful reasons for collecting this kind of data.

Always ensure you're aware of which international laws apply to the collection and processing of sex, gender and sexuality data.

In conclusion

I hope you've found this helpful.

If you notice something I haven't quite got right, I really (really!) do want to hear about your feedback. I am striving to continue learning about these important topics, and am grateful to Mel Mason and Joanna Mills who have written to me to share their feedback and ideas. If you have any recommendations or suggestions, please feel very welcome to contact me here.

Resources

-

The A-Z of Gender and Sexuality by Morgan Lev Edward Holleb – A deft, nuanced and lucid exploration of queer and trans identities which is in equal measure empowering and political. I learned so much reading this book and couldn't recommend it more highly. Available at the Gay Pride Shop.

-

List of LGBTQ+ Terms by Stonewall. A straightforward place to familiarise ourselves with LGBTQ+ terms, from Europe's largest LGBT rights organisation.

-

Nonbinary: Memoirs of Gender and Identity by Micah Rajunov and Scott Duane – if you're keen to learn more. A collection of essays, each of which is very readable and well-written, offering broad insights and perspectives on non-binary identity. Available at the Gay Pride Shop.