The Paradox of the Ship of Theseus

The Ship of Theseus is an ancient Greek thought experiment about identity and identity change. It was first recorded by Plutarch and famously discussed by the likes of Heraclitus and Plato.

Central to this paradox is a ship associated with Theseus, which, over time, had each of its wooden parts replaced as they wore out.

Eventually, every single piece of the ship was replaced with a new one, leaving us with a puzzling question:

Is this renovated ship still the same Ship of Theseus, or has it transformed into something entirely different?

The ontological status of the ship

That's philosophical jargon for "what's the nature of the ship's being and identity?"

There are three possibilities:

1. The ship is still the Ship of Theseus

If this turns out to be the case, we must then ask:

How did the ship maintain its identity? Why?

2. The ship is no longer the Ship of Theseus

If this turns out to be the case, we must then ask:

When did the ship cease being the Ship of Theseus? Why?

3. There never was a Ship of Theseus

If this turns out to be the case, we must then ask:

How do we explain our perception that the Ship of Theseus ever existed?

The Ship of Theseus is mythical, but the thought experiment draws parallels with things we care very much about. Like ourselves. Human cells are completely replaced roughly every seven years, yet we want to argue we retain our identity, just like the Ship of Theseus.

Two ships

Thomas Hobbes extended the puzzle centuries later.

If we gathered all of the old planks and used them to build a second ship, which ship – if either – would be the original Ship of Theseus?

Two Ships of Theseus? Or one? Or none? Credit: Author, Midjourney

We now have four possible answers.

- The restored ship is the Ship of Theseus

- The re-assembled ship is the Ship of Theseus

- Both ships are the Ship of Theseus

- Neither ship is the Ship of Theseus

Beginning to solve the paradox

Let's start by asking – what constitutes the identity of the ship? We have a few rough options:

- Materialist view: The physical components of the ship make up the Ship of Theseus

- Structuralist view: The arrangement of the physical components make up the Ship of Theseus

- Culturalist view: The history and cultural significance determine the identity of the Ship of Theseus

The materialist view

The materialist view is that the identity of an object is tied to its physical components.

According to this perspective, the Ship of Theseus retains its identity as long as the original materials remain. Once a single component is replaced, the ship loses its identity as the original Ship of Theseus. Variations of materialism have been defended since all the way back in ancient Greek philosophy by the likes of Aristotle, and since by the likes of Locke and Van Inwagen.

The idea has strengths. There's something intuitive about the idea that if you replace all of the original materials of an object, the object's identity has changed.

But there's something of a lack of practicality about the materialist approach. In real life, things we think of as objects require repairs and replacements all the time, but we don't think they've changed their identities.

My car, Robin (yes, I named it) had to have a new suspension arm the last time it went to the garage, but I certainly still think it's still Robin. Perhaps some parts are more fundamental than others. Maybe we can change Robin's tyres as much as we like without Robin losing identity, but that some parts are more fundamental than others, like the engine. Some have defended more nuanced essentialist views like this.

Robin? Credit: Author, Midjourney

But what about the structuralist and culturalist views? Before we get into these, I want to add some more technical colour by distinguishing between two types of identity.

Strict Identity vs. Loose Identity

In philosophy, there's a distinction between strict identity and loose identity. Understanding it will be useful here.

Strict identity follows the principles of Leibniz's Law – also called the Identity of Indiscernables, which states that if two objects are identical, they must share all the same properties.

Loose identity allows for some changes in the object while still maintaining its identity.

This notion of identity is strict and inflexible, and doesn't really translate well to real-world situations where objects undergo changes over time.

Loose identity, on the other hand, permits some alterations in an object's properties while still preserving its identity. This is the more common way we talk about objects in everyday language.

We could say, if we wanted to, that the Ship of Theseus remains the Ship of Theseus in the sense of loose identity – explaining why we can still refer to it in everyday discourse – but that it loses strict identity.

Culturalism

We're now in a position to discuss the culturalist view. This is the view that the history and cultural significance determine the identity of the Ship of Theseus. When we talk about the ship through the lens of culturalism, we're generally interested in loose identity.

Under the culturalist view, the renovated Ship of Theseus would still be considered the same ship because it retains its connection to the original ship through its history and the shared understanding of its significance. This view allows for the notion of continuity and preservation of identity through the context in which the object exists.

However, the culturalist view has its own challenges. For instance, it raises questions about the role of individual perspectives and cultural biases in determining an object's identity. What happens when the cultural understanding of an object shifts or when different cultural narratives clash in their interpretation of an object's identity?

I find it rather unpalatable to think that objecthood – in the strict ontological sense – can be defined by the way humans think about it. Human experiences and perceptions, I think, fails to carve the world at the joints.

There's still an interesting debate to have, though, about how we confer (loose) identity through social consensus.

Structuralism

Let's look at another more ontological option – the structuralist view.

Perhaps the structure and form of an object are more important than its physical components.

That would mean maintaining the same structure, even with different materials, would preserve its identity.

This viewpoint allows us to account for changes in an object's physical components while still maintaining its identity, as long as the structure remains the same.

But there are problems with structuralism. Let's look at two big ones. We'll start with the problem of vagueness (which is also a problem with materialist views) and then look at the problem of multiple identical objects.

The Sorites Paradox and vague identity

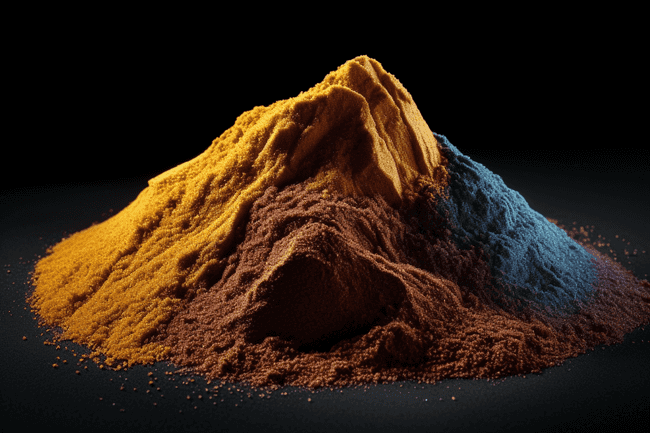

When does a heap of sand cease to be a heap, if we remove grains one by one?

The Sorites Paradox Credit: Author, Midjourney

This is the Sorites Paradox, or the "paradox of the heap". The paradox exposes the vagueness of our language and concepts when dealing with identity.

As we replace parts of the ship, it's difficult to pinpoint the exact moment the ship loses its identity. Some philosophers argue that this vagueness is a feature of our language and cognition, rather than an inherent property of objects themselves.

There's another thought experiment in metaphysics introduced by philosopher Peter van Inwagen.

Lumpl is a lump of clay, while Goliath is a statue made from that same lump of clay.

Are they the same object or two distinct objects?

When is the lump of clay no longer a lump of clay? Credit: Author, Midjourney

If they are identical, then any property that Lumpl has, Goliath must also have, and vice versa. But there seem to be differences between the two, such as Goliath having aesthetic properties that Lumpl lacks.

Both the Sorites Paradox and the Lumpl and Goliath thought experiment reveal that our language and cognition may not be well-equipped to handle such complex and nuanced issues. Perhaps this vagueness is a feature of our language and cognition, rather than an inherent property of objects themselves.

Four-Dimensionalism: A satisfying solution?

Four-dimensionalism proposes that objects extend in time as well as space, forming four-dimensional "space-time worms".

The four-dimensional Ship of Theseus is a series of slightly different, temporal parts of one four-dimensional object.

Each stage of the ship's existence, from construction to alteration, is part of this four-dimensional entity.

If that's right, then the renovated ship and the reassembled ship are different temporal parts of the same object. Both ships are the Ship of Theseus, but distinct temporal sections of it.

The four-dimensional view also offers a truthmaker for propositions we want to claim about the Ship of Theseus. For example, "The Ship of Theseus was built in Athens," is made true by the early stages of the Ship's four-dimensional existence.

The theory has intriguing implications for understanding things like personal identity.

Just as the ship, we humans consist of a series of temporal parts making up our four-dimensional 'self'. This perspective recognizes each moment of our existence as a part of our interconnected four-dimensional being.

Wrapping up

The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment, but you and I are not. We feel we want to satisfy our intuition that we are numerically identical to ourselves when we were three years old. Preserving that intuition turns out to be complicated.

For what it's worth, I'm happy to say there is no fact of the matter about at what points the Ship of Theseus is the Ship of Theseus, and indeed, when it is not.

I'm an existence monist, and believe – roughly – that only one object exists, the universe, and that the things we perceive of as objects are simply subregions of spacetime.

That means that to me, "the Ship of Theseus" is just a convenient fiction that we use to pick out a particular subregion of spacetime, but that the issue of defining where those boundaries are is a problem of language. Strictly, the Ship of Theseus does not exist.

And yes, if you're wondering if I'll bite the big bullet – I will. I also do not believe that I [strictly] exist.

Enough of that for now, but I defend existence monism from the incredulous stare here, explain how truthmaking can work here and wrote an entire dissertation on it here.

In the end, even if we were to accept that objects like the Ship of Theseus are "convenient fictions," these fictions have real-world consequences. They shape our interactions, our morality, our laws, and our self-understanding. We may not be able to pin down the essence of identity or locate the precise boundary where one identity becomes another, but that does not make the journey any less worthwhile.

Further reading/watching

Advanced book: Writing the book of the world – Theodore Sider – All about structure, or "joint carving," and how it underpins our understanding of the world. Challenging but rewarding. Available from Wordery

Introductory book: Metaphysics: An Introduction – Jonathan Tallant – An accessible introduction to a range of topics in metaphysics from the person who kindly supervised my dissertation. In particular, he covers material constitution, told through the lens of truthmaking. Available from Wordery