Today, I just want to take a moment to appreciate something really quite extraordinary!

I've loved cosmology for as long as I can remember. In 2012, an app accompanying Brian Cox' TV series, Wonders of the Universe, was released. I bought and downloaded it, and whiled away many a happy hour.

One thing struck me, and stuck with me, more than anything else. It was this:

“The arrow of time has created a bright window in the Universe’s adolescence during which life is possible, but it’s a window that won’t stay open for long. As a fraction of the lifespan of the Universe, as measured from it’s beginning to the evaporation of the last black hole, life as we know it is only possible for one-thousandth of a billion billion billionth, billion billion billionth, billion billion billionth, of a per cent.”

That. Is. A. TINY. Amount.

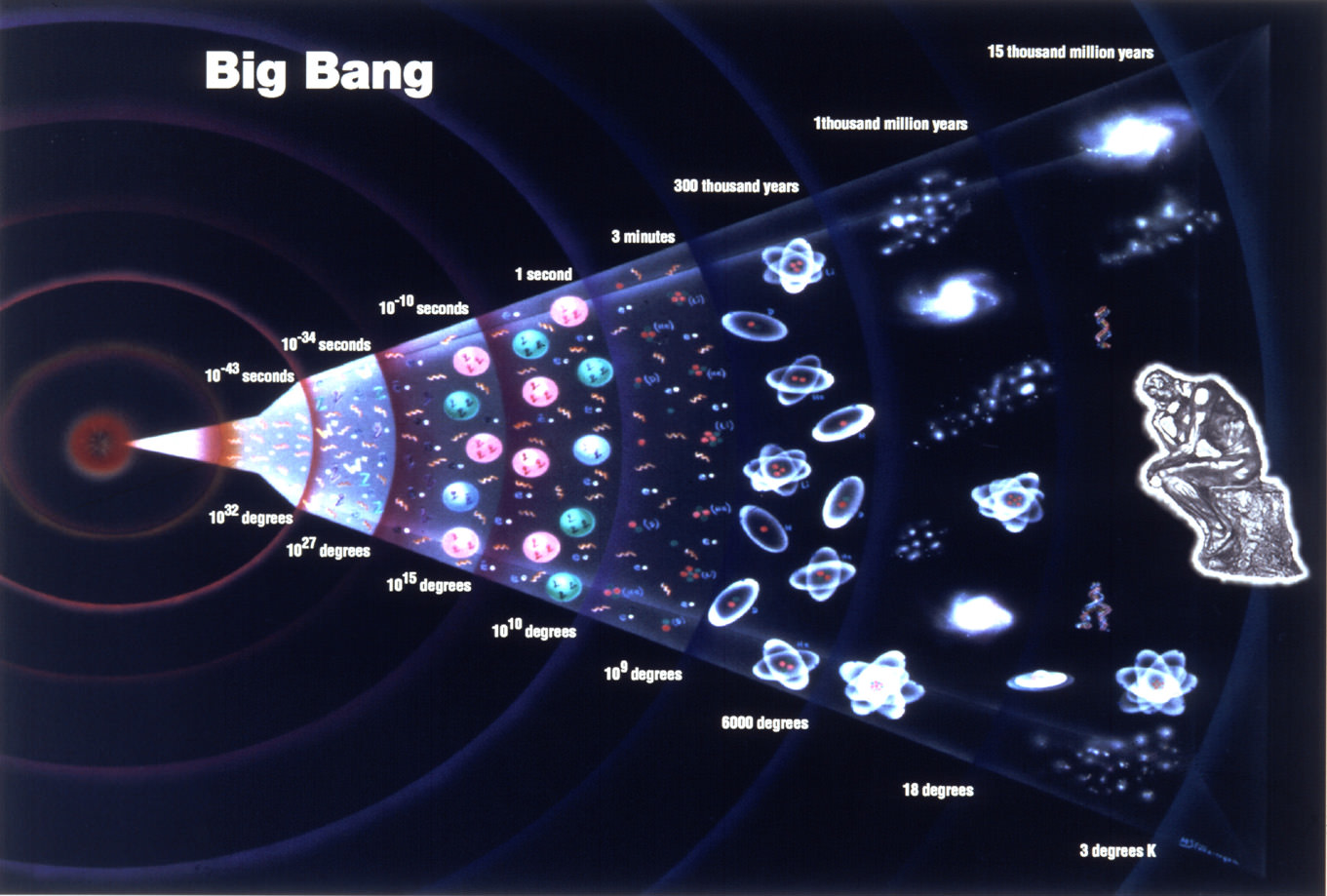

Telling the story of the universe parades the most outrageously large numbers and extraordinarily unlikely ratios in ways that make the mind boggle.

Getting a sense for scale

Just one second after the big bang, the universe was a few light years across (possible since the conjecture that physical objects cannot travel faster than light is often misconstrued to be that nothing can travel faster than light, which is not the same.) Bear in mind that when the universe was around one hundredth of a billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second old, it was smaller than a subatomic particle.

In this same amount of time, the very first element, helium, was born.

But it took over 200 million years for gravity to pull clouds of dust into the first galaxies.

Earth was born 9 billion years later, and a few more billion years after that, humans walked the earth.

But the conditions for life won't be there forever. In fact, there's probably only 100,000,000,000,000,000 years of viable life time. That sounds like rather a long time, but hold your horses...

Eventually, the universe will fizzle out. The last stars will have died long ago, and their remains sucked into black holes. The work of the Second Law will be done - entropy will finally stop increasing, because everything will be maximally disordered. Nothing will happen, and nothing will continue to happen, forever. But that is going to take rather a long time indeed. In fact, it's going to take around 10, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000 years - give or take.

Visualising it

So - going back to Professor Cox - what would that fraction of time that life is possible for look like on a timescale? Let's try and visualise that!

Let's start with the part where life is possible. We'll say that it's 1 cm long, and this represents the amount of time where life can exist. If Cox is right, then this 1cm section is one-thousandth of a billion billion billionth, billion billion billionth, billion billion billionth, of a per cent of the whole time line.

So that is, I think (I'm not a mathematician), 83 zeroes after a decimal point followed by a 1. Mathsy people might say 1x10^-83 (again, I think..!)

Or if you prefer: 0.000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,0001.

Knowing that, we can work out the length of time in total.

We would need a chart 1x10^83 cm long - or 1x10^81 m long - or 1 followed by 81 zeroes.

Or: 10,000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000! That's a lot of metres.

In fact, the observable universe is only 1^28 m wide, apparently, or 1 followed by 28 zeroes.

That's just 10, 000,000,000, 000,000,000, 000,000,000!

In other words, this graph would not fit into the observable universe, but the section representing the time within which life will be possible would be all but 1cm long...

Even if these numbers are a bit off because our science isn't perfect, or if my maths is a bit off because I haven't done powers since I was 14, a little shift either way won't make any difference, there is no way we are going to be drawing this graph..!

Even if we say we're going to make the section representing "life possible" a fraction of a cm, it still isn't going to fit into the observable universe. We'd have to make divide the centimetre by 10, 52 times, in order to make the scale of the graph small enough to fit inside the observable universe (just..!) - and that is smaller than an atom (which is 1×10^−10), by quite a lot..! Not a very useful timescale, then...

Humbling facts

Spectacular stuff, isn't it?

I'll finish up with a few of my favourite words from Professor Cox:

The most astonishing wonder of the Universe isn’t a star or a planet or a galaxy; it isn’t a thing at all — it’s a moment in time. And that time is now.

"Just as we, and all life on Earth, stand on this tiny speck adrift in infinite space, so life in the universe will only exist for a fleeting, bright instant in time. But that doesn’t make us insignificant, because we are the cosmos made concious. Life is the means by which the universe understands itself.

"And for me, our true significance lies in our ability, and our desire to understand and explore this beautiful universe."