I've spend the last seven years of my career in start-ups, from early-stage to emerging scale-up. Two were VC-funded. And it's been obvious that the typical cookie-cutter advice and benchmarks around the internet don't quite apply in the same way.

We can't just Google "what should our Customer Acquisition Cost be". The right answer for us at our growth-driven start-up won't be the same.

That's because, firstly, we don't have the same data available to us, and secondly, our goals aren't the same as typical businesses.

The earlier-stage we are, the more true that often is.

So I want to chat about three golden growth metrics, and how they behave at start-ups: Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), Lifetime Value (LTV), and the CAC:LTV ratio.

When we understand how they need to work, we're giving ourselves power – the power to choose the right things to try that don't scale, to chart a path to grow sustainably, and, yes, get ourselves in a position to reach that next funding goal or profitability.

I don't claim to be an expert – I'm just sharing knowledge and experiences I've picked up over time. If you've got thoughts or feedback, please feel very welcome to get in touch!

1. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

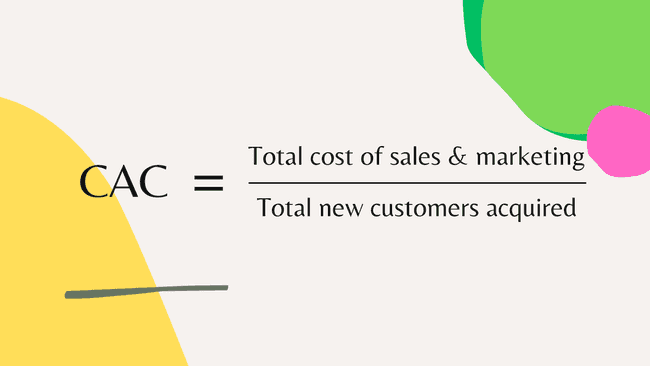

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) measures the total cost of acquiring a new customer.

To calculate CAC, also called Cost Per Acquisition or CPA, we divide the total marketing and sales expenses by the number of new customers acquired in a specific period.

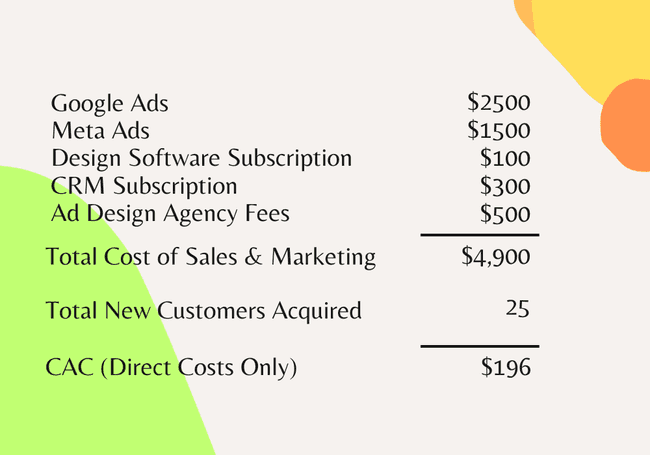

Simplified CAC calculation

Traditionally, marketers will segment CAC, and use it to indicate which tactics, strategies and campaigns are working. A lower CAC indicates we're getting a better return on our investment (ROI). Leadership are more likely to find a blended CAC useful.

At start-ups, the metric can do even more heavy lifting – we can use CAC to assess the success of experiments and develop a fuller picture of what channels and tactics work. More importantly, we can compare CAC to the lifetime value of each customer (more on this later) to help us predict the sustainability of our growth, set budgets and more. And it's a core metric for our conversations with investors. As we grow, we use CAC – typically blended CAC – as an indicator of overall business health.

What should be included in CAC?

What we include in CAC depends on what we're using it for.

Typically, writers on this topic will tell us that CAC should capture direct costs associated with both marketing and sales. But we have to decide whether we're including indirect costs.

That'll mean that by default, we're including costs like:

- Ad spend

- Tools

- Sales-related costs

- Fees for outsourced services

- Production costs

Generally, these will suffice in a marketing context.

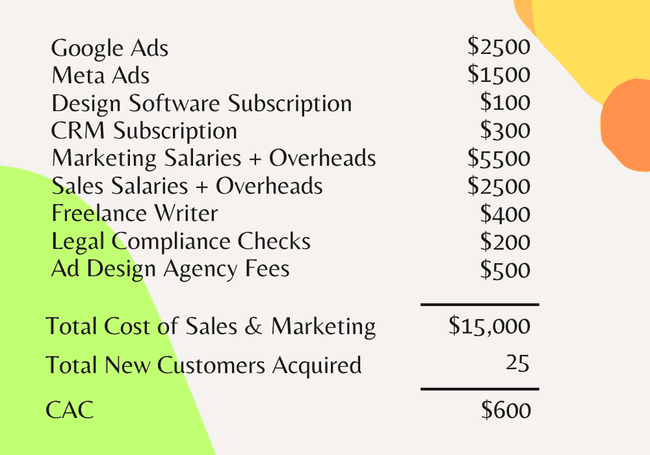

But I think the main use cases for CAC at start-ups – and particularly VC-funded ones – call for a more comprehensive calculation if it is practical.

We can use it as a growth indicator to signal the effectiveness of our growth strategies.

Leaders and investors need an overall view of how we're investing for growth, so if we can, we should consider more than just the direct costs above. First, whether we're considering it a direct or indirect cost, we should consider including the salaries of people actively involved in acquisition, along with a range of other indirect costs, such as employee overheads, legal services for marketing and sales and more.

A simple example of CAC at a B2B SaaS company including indirect costs

When we're operating a small business, we need to be efficient at all levels of the business. We can only measure this efficiency when we include all related costs. Compare the CAC in the same example when we exclude those indirect costs and salaries – it's clear why this gives a skewed image of CAC.

CAC excluding indirect costs

An important caveat though: it's not always practical to be this comprehensive when we're early stage. That's ok. Keeping simple and focussed can be the right move when resource is limited. But we have to be aware of any larger costs that might be eating away at our numbers in the background.

Keeping the calculation simple and focused on direct acquisition costs might be more practical.

Meanwhile, if our use case is just comparing the performance of paid marketing channels, I'd probably be excluding salaries.

What should our CAC be?

Sorry – cop-out incoming! It depends.

We're best off thinking about CAC in relation to the value that each customer brings over the lifetime of their relationship with our business (the lifetime value, or LTV).

We haven't talked about LTV yet, or the relationship between the two – so let's get into that now.

2. Lifetime Value (LTV)

At start-ups, we need to develop an idea of the value of a customer over the course of their relationship with the business quickly. This is Lifetime Value, or LTV, also called Customer Lifetime Value or CLV. It helps us evaluate and project key things like long-term profitability.

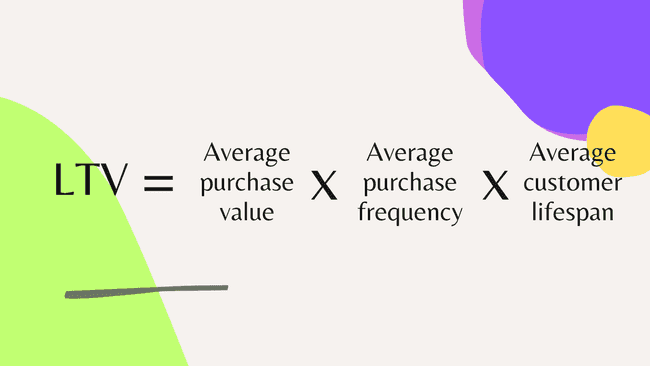

Lifetime Value (LTV) measures the total revenue a business can expect from a single customer throughout their relationship with our company.

Simplified LTV calculation

That's simplified – in reality, how we calculate LTV depends on our business model...

How should start-ups calculate LTV?

This is tough! I've found that sitting down with sparse numbers and trying to apply one-size-fits-all wisdom doesn't achieve much.

We usually just don't have the data we need to accurately predict LTV.

The second challenge is that, much more than more mature businesses, we have to account for future change and growth. That growth might come in all kinds of shapes and sizes. We're probably planning for volume growth. Maybe we have new products or services lined up. Or perhaps we're trying to break into new markets. Basically, we have a lot of variables, and poorer predictability.

But we need LTV to assess long-term business viability, and potentially demonstrate returns on investment to investors.

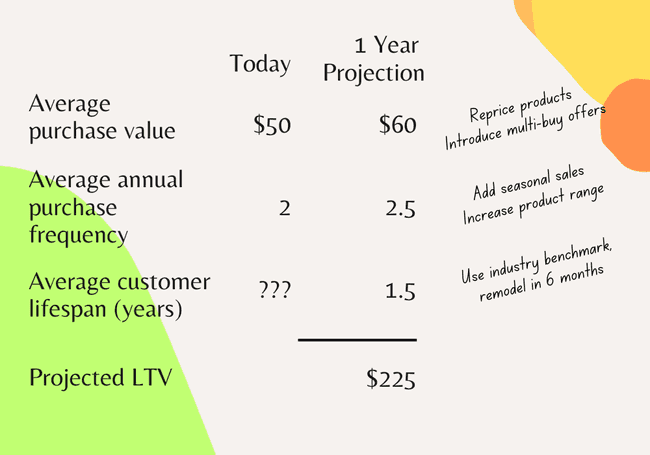

Most teams calculate LTV based on the average purchase value, purchase frequency and average customer lifespan.

When we use LTV for our start-up, we have to do things a bit differently. Here are some things I think about when modelling:

- What's the average purchase value + how might it change?

- What will the purchase frequency be?

- Are any new products/services expected to change the above, or lead to further purchases?

- What retention strategies are planned? What might the impact be?

- What's going on in the market?

It's all going to be a lot more speculative since we can't rely on established patterns. Everything has to be contextualised within our specific growth trajectory and market potential.

Simplified LTV workings for a B2C eCommerce business

But a word of warning: over-optimism is dangerous (my fingers have been thoroughly burned – but I've also learned that the vast majority of directors and founders will tend towards over-optimism. Same with assuming sales will close, if that's familiar..!) Forward-looking assumptions need justification. Avoid those "finger in the air" temptations.

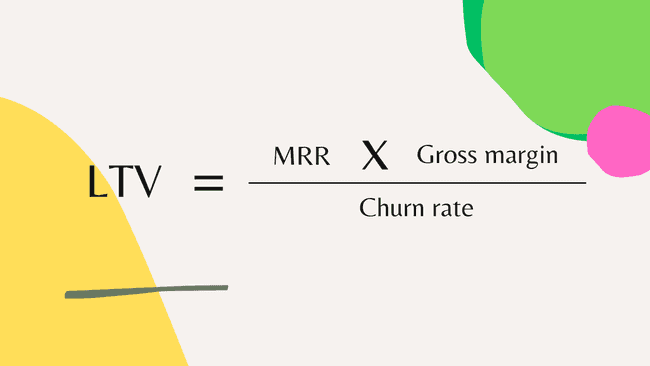

For subscription models, we have to make the calculation based on our expected monthly recurring revenue (MRR), and consider our expected churn rate.

Simplified LTV workings for subscription-based businesses

Finally, while a more typical use of LTV might not need it (e.g. using LTV in marketing), consider taking into account direct costs like hosting and support. It'll give a more accurate picture of how scaling needs to happen and how healthy the relationship between CAC and LTV is – more on this very shortly.

How to go about improving LTV

I used to work at a tech education start-up which essentially sold one product. We spent years working out how to extend our relationship with our customers, and it involved all kinds of stuff, from expanding our set of products, working out how to get customers to chain purchases, improving the support and playing with pricing.

I come from growth marketing, and I think the growth marketing approach – particularly, being concerned with the entire customer lifecycle, not just acquisition – is what is needed here for many start-ups.

But the step before that is establishing product-market fit. If we've not found product-market fit, we're going to struggle to make our maths work out.

There will be many others, but some of the big levers we can pull include:

- Segmenting customers to tailor our strategy and focus on better-performing segments

- Enhancing the customer experience (purchase process, customer support, product quality)

- Retention strategies (loyalty programs, value-add, new products)

- Personalised experiences (data-driven journeys, personalised marketing, product recommendations)

- Pricing strategy

When we have delighted customers, we're likely to increase LTV.

3. The CAC:LTV Ratio

The CAC:LTV ratio helps us compare the value of a customer and the cost of acquiring them.

If your ratio is 1:3, then your lifetime value is three times the cost of acquiring a customer. It means that for every $1 you spend, you get $3 back.

Generally, businesses use LTV:CAC to decide how to allocate budget for marketing, sales and customer service.

In growth marketing, we can use it to tell whether the investment in acquiring customers is yielding proportional returns in terms of customer value.

Leaders can use the CAC:LTV ratio to help tell whether spending on customer acquisition is sustainable and if it aligns with long-term profitability goals. This ratio (and these metrics) are super useful for modelling scenarios, and planning for them – doing this shows how different strategies could impact our future financial health.

What start-ups should look for in CAC:LTV

When we're in a start-up, we have to think about CAC:LTV in a different way than we otherwise would.

Outside of start-ups, a healthy ratio would be one where the lifetime value of a customer significantly exceeds the cost of acquiring them. It's a bit unhealthy to generalise, but as a yardstick, we might expect it to take around a year to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer, and a ratio of 1:3 is broadly considered to be roughly ideal. Really though, what a "good" CAC:LTV ratio looks like depends very heavily upon our industry and business model.

Early-stage startups might have a lower ratio due to aggressive growth tactics. And this is usually acceptable to investors.

The conventional wisdom just doesn't apply in quite the same way at start-ups focussed on rapid growth.

When we're focussed on rapid growth, it's acceptable to do things that don't scale, when we have a good reason. Obviously, we have to make these decisions in the context of our cashflow and burn rate.

I've spent time with a SaaS startup that were still confirming product-market fit. Feedback and close relationships with customers were far more valuable than the expected revenue, so we were willing to pay much more than usual for an acquisition. Each customer was an invaluable opportunity to learn, test the conversion funnel and the sales process, and improve the product.

I can think of a number of other good justifications for a lower CAC:LTV ratio. Here are a few – there will be many more!

- Building close customer relationships in return for feedback

- Going for the word-of-mouth approach

- Going hard on getting early traction

- Looking for traction for new markets or products

- When there are clear positive signs the lifetime value of customers is high

- To get the edge in a very competitive market

- For a highly strategic partnership that is going to open doors

While I was with one of my start-ups, our CAC:LTV ratio for one channel – LinkedIn outreach – was abysmal. It was something like spending $1 and getting $0.05 back. But we got 10 early customers who gave us invaluable feedback over a critical period of product development. In the end, we realised none of them fit our ideal customer profile and they all churned, but it was worth the cost, probably many times over.

When we do things like these, a lower CAC:LTV ratio won't be an issue.

But if I'd spent $1 on that campaign and get back $1.50 with no other gains, I'd say it was a waste of resources (both time and money).

Naturally, the goal and focus has ultimately got to be reaching a sustainable, healthy CAC:LTV in due course. We have to keep checking ourselves for getting reliant on things that don't scale and have a plan to phase them out.

Remember that if you're not including net profit and costs in LTV, when using CAC:LTV for high-level strategic purposes or financial reporting, we have to factor those in. Otherwise, we can't tell if the business model is sustainable.

When CAC:LTV looks low

As we scale, it becomes more important to bring our CAC:LTV ratio towards a healthy benchmark.

A low CAC:LTV (relative to our benchmark and growth stage) is telling us that we're spending too much to acquire customers, relative to the value they're bringing.

In this situation, I'd be asking:

1. Do we have inefficiencies in the sales funnel? Perhaps our sales cycles are too long, or perhaps there's a disconnect between our marketing messages and the actual sales process. It could be a sign our targeting is off, too.

2. How can we optimise our acquisition strategies? Are we relying on channels with a high CAC – and can we bring those costs down without sacrificing quality leads? What new channels and tactics could be trialled? Can we invest more in channels with a low CAC?

3. Can we improve our products or services? Perhaps there are ways for us to improve our value proposition. If we can do that, maybe we can increase spend or increase purchases per customer. We might also consider our pricing strategy.

When CAC:LTV looks high

This is a great problem to have, especially for a start-up. But it can be a sign we're missing opportunities.

Why? Well, if we're spending very little to get new customers, and customers have a high value over their lifetime, we could be under-investing in getting new customers.

In other words, a high CAC:LTV means we may have untapped growth potential.

How we tap that potential is of course a big strategic conversation, but we might consider things like investing more in customer acquisition, or looking into new markets or products.

Quick word of warning though – before acting on a high CAC:LTV, be sure to know what's driving it! If it's the result of short-term tactics that don't scale, those need to be dealt with first.

Wrapping up

When we're wrestling a start-up, we have to adapt metrics and use them in a way that makes sense for our unique journeys.

The conventional wisdom that suits established businesses doesn't always apply in the same way.

But when we use them right, CAC, LTV, and the CAC:LTV ratio can give us plenty of power.

I don't claim to be an expert, and I'd love to hear your thoughts. Do you agree with these insights, or do you have a different perspective? Have any of your own words of widwom? Please get in touch with me here!