Originally published on 23/01/2018, and updated 07/05/2023

They’re all around you... Or so it seems.

Our goal is to answer the question: “When is something an object?”

It’s a question that’s baffled philosophers for centuries. When you start to really think about it, you realise it’s not as straightforward as you were hoping.

Let’s get started.

Is a pen an object?

Imagine you’ve got a pen. A pen is a great candidate for an ‘object’. On the face of it, it’s cohesive and stable; you can hold it in your hand, throw it; it’s an object in any normal sense of the word!

With this in mind, let’s come up with our first definition for an object as a starting point. It’s open to revision, but here it is:

“An object is something which holds together — it is cohesive.”

Ok! That’s a start.

Devil’s Advocate: “But what if it breaks? Your pen’s made up of a few bits and pieces — the casing, the ink cartridge, the nib, the spring…”*

This gives us a new problem. When the pen breaks, one object could become two, three or four. A similar problem would arise if you smashed a brick or took apart a car. We must wonder — how many objects were there to start with? Four? As many parts as there are molecules? Atoms? Even more than that?

Devil’s Advocate: “So how can you say a pen is an object? A pen, as you’ve just seen, is in fact lots of objects — an arbitrary number!”

Well, okay. So maybe we need to bring in a new idea: composition. However many bits and pieces you think there are in the pen doesn’t matter — all those little pieces compose to make a new object: the pen.

Now we can say it’s true that there’s an object which we call ‘pen’, even though it’s true that the pen is also composed of smaller objects.

Devil’s Advocate: “Fine. You have me there. But let me ask you a few questions: when do objects compose? You say the spring, the case, the cartridge, compose… Well — what about the molecules of air inside the pen? Are they part of the pen? If I glue an embellishment onto it, does that become part of the pen? If I place two pens side by side and put a rubber band around them, do I create a further object? If I replace the spring in the pen, is it the same pen?”

Wow… Slow down! One thing a time!

When do objects compose?

That's what philsophers call the Special Composition Question.

We clearly need an answer to this, otherwise we could say anything composes. (that’s called Mereological Universalism, and it does actually have its advocates! We end up making very strange claims such as “there is an object which is a-sixpence-and-the-moon”. If everything composes, the moon and I compose to make an object. So does your car and my copy of Wuthering Heights. That’s an object. So yes, it seems we ought to limit what can compose!)

Views of objecthood

There’s a few questions posed above.

- One: where exactly do we draw the boundary of an object?

- Two: what level of proximity might constitute objecthood, if any?

- Three: what level of attachment might constitute objecthood?

- Four: How much of an object can we replace without it becoming a new object?

Drawing the boundaries

Let’s deal with Question One first. Where do we draw the boundaries of objects?

Well, many would be tempted to draw it at some level which had some scientific significance. For example, we might choose the molecular level — the boundary of the object is defined by the border of the molecules which compose the outer layers and the ionic bonds binding atoms together.

But the more we zoom in, the fuzzier the picture gets.

As we know, a staggering 99.9999999999996% of a hydrogen atom is empty; and an approximated 9.9999999999999999999958% of the universe is empty! And of course, electron shells (the orbit level of electrons around the atomic nucleus) are almost entirely empty too. So where can we really draw the boundary?

Here’s another option: we might say that defining objects should be done only when it is useful for us, as humans, to do so — therefore the boundary should also be only as close as it needs to be for it to be intuitive to humans. If the latter is true, then we’re saying that the definition is dependent on us, rather than it.

Devil’s Advocate: “That’s not a claim about the nature of the object though! And that’s what we’re looking for isn’t it? An answer to the question 'what is an object', not 'how to humans define objects'.”

She’s quite right. We are indeed looking for an answer to the former. But we still may be onto something here. Maybe there is really no such thing as an object itself (independent of human existence) because any boundary-drawing, or ‘carving’, of reality is arbitrary. It could just be a useful fiction to help us navigate the world. Let’s hold onto that thought.

Does proximity matter?

Let’s look at Question Two. What level of proximity, if any, constitutes objecthood?

This one’s easier. Very few philosophers are going to endorse the view that proximity is grounds for objecthood. They might be tempted to say it’s a good indicator, or perhaps that it is a necessary condition for objecthood (but probably not sufficient for objecthood). By that, I mean that all parts of objects are by some definition “close” to the other parts, but that isn’t enough to say something is an object.

Take this example: let’s assume my pen is an object. If contact is sufficient for objecthood, then when I put it in my hand, myself and the pen become an object. Me-and-the-pen is an object. But I’m also sat on a chair, which is on a rug, which is on the living room floor. By that logic, Me-and-the-chair is an object, and Me-and-the-chair-and-the-rug is also an object. You can probably see by this part that this logic takes us to some strange conclusions. Besides, the same point about the emptiness of atoms and space applies here. Really, nothing even touches at all!

What about attachment?

What about Question Three? Is attachment sufficient for objecthood?

We run into problems here too. We’ve just said nothing really touches. Indeed, that makes it difficult for things to be attached, too. How set does the glue between two objects have to be in order for it to count as ‘attached’? This idea of attachment seems to be a useful linguistic device used by humans to denote things which, by human standards, cohere.

But there’s more. Think about the pen: the parts are not actually attached at all! They’re just shaped in a way such that they can’t fall apart or move out of place. There aren’t any adhesives holding it together.

The Ship of Theseus

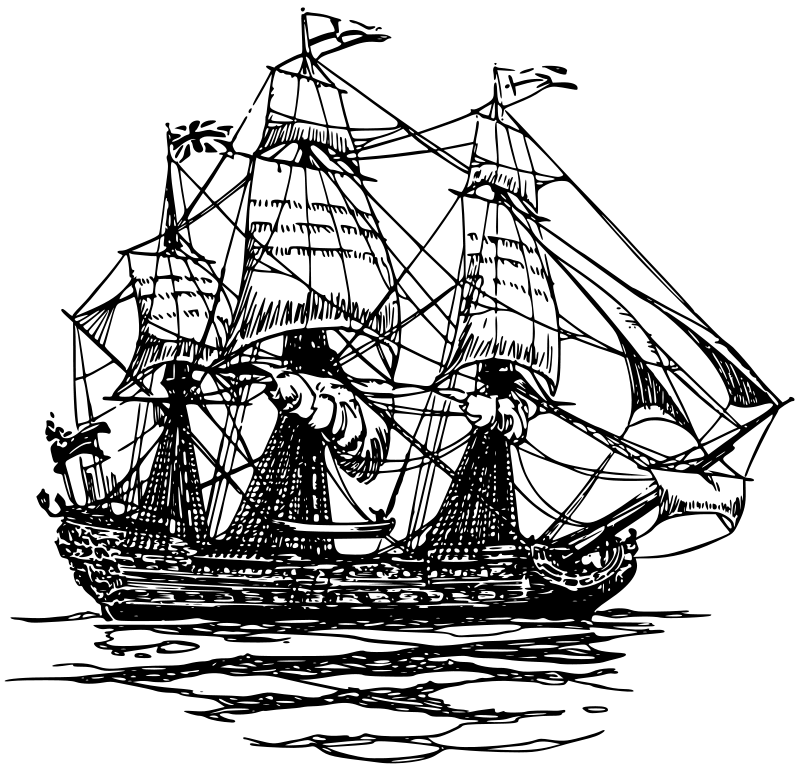

Finally, let’s tackle Question Four. How much of an object can we replace without it becoming a new object?

This time, we’re not just talking about identifying an object, but working out how to identify one through time. And this presents problems of its own.

There’s a very famous ship amongst philosophers called the Ship of Theseus. According to the Greek legend documented by Plutarch, Theseus’ ship had its planks replaced as they decayed — so much so that eventually the ship is made entirely of new planks. Here’s the clinch: is it still the same ship? Some say so, some say not. In the 17th century, Thomas Hobbes extended the puzzle. If the original planks were gathered and made to build a new ship, which would be the original?

It’s really tricky, and the intuition again is that the ship was never really an object at all. Its planks could have been, but planks can also be broken up and remade, and so the problem regresses. This problem is, again, altogether circumvented through the acceptance that there’s no fact of the matter, in reality, as to when objects compose.

A better solution

So here’s a thought.

However we’ve tried to define the boundaries, we’ve found that the way we carve reality has been arbitrary.

It seems that there’s nothing about reality which makes it clear where one object ends and another begins, or when objects compose larger objects.

But there’s lots to suggest we still need the concept of objecthood — humanity depends on the idea completely! So objecthood as we know it (of chairs and tables and pens) is not a metaphysical (to do with facts about reality) problem, but a linguistic (to do with facts about language) problem.

Metaphysically speaking, it could be that there’s no such thing as an object. It’s just a useful linguistic device to help us navigate the world and our lives. In metaphysics, there may be no actual boundary between one object and the next.

What would a reality like this look like?

Well — the things that we call ‘objects’ could just be characterised as regions of spacetime. These areas of the universe (‘pens’, ‘chairs’, ‘planets’) are given names by humans to help them navigate life. Everything that exists is just an area of the spacetime manifold.

Devil’s Advocate: “Right. But if that’s true, couldn’t the entire universe still be said to be an object? Something has to be!”

Right!

And that’s a view called Existence Monism. It’s the view that there is one, and only one, object: the universe. All the so called ‘objects’ inside it are just spacetime sub-regions of the universe.

It’s not the only candidate out there. If you’re interested, there’s a view called Mereological Nihilism which is a lot simpler than it sounds: there are no composite objects at all (objects composed of other objects), the only objects that exist are the smallest possible units, which philosophers call ‘mereological atoms’. Don’t confuse them with atoms in the scientific sense. Mereological atoms would be much, much smaller; the smallest possible thing. And they never compose a further object. The universe would just be a collection of these atoms on this view.

Wrapping up

So there you go. A whistle-stop tour of when something is an object.

Philosophy is something that is done, rather than read. I’m sure, as you’ve been reading, you’ve had a thought or two on some of the debates I’ve presented. Maybe you disagree with some aspects of the argument. Maybe you think there’s a reason to think an idea is implausible. Or maybe you think that the terms of the debate need a more careful definition. That’s great! You’re already doing philosophy.

I have provided links to some further reading above if you’d like to learn more. What do you think objects are? What do you think constitute objects? Let me know what you think Twitter!

Undergraduate of Philosophy? I wrote a dissertation in 2014 on Existence Monism which is partly motivated by the difficulties surrounding defining objects.