Over the summer, my colleague and I went to the InnovateHer Summit, a meeting of the InnovateHer network to discuss diversity and inclusion in tech. InnovateHer provide educational programmes for girls aged 12-16 to give them the confidence and skills they need to pursue a career in tech.

Amy Lynch, the Head of Diversity & Inclusion at ThoughtWorks was invited to speak on unconscious bias. We learned a few really important things, so I decided to do a bit of my own research, and in turn - since this is such a crucial topic - share it with our community.

We are all biased

Our brains have so much information pouring into them that it's impossible to process it all. In fact, according to Timothy Wilson, 11 million bits of information pour into our brains at any one moment, but can only process 40! To help us out, our brain creates shortcuts based on our past experiences to help us process information quickly.

This is really cool! It can be incredibly helpful. It probably saves our lives regularly. It helps us jump out of the way of buses, type without thinking and remember the lyrics to songs we haven't heard for a decade.

But it can also tempt us to make incorrect and/or immoral assumptions which we often don't question. It can make us biased.

Luckily, being aware of our own bias helps us tackle this head on. Here are a few of the most important biases I've learned about.

1 - Affinity Bias

Affinity bias can be thought of as the "like me" effect.

We want to spend time with people that we have something in common with. That's fine and good, but we need to be aware of some of the consequences. This phenomenon extends to the workplace, where it can be problematic.

Company's interview processes are usually hooked up to establish "cultural fit". Unfortunately, this idea is prone to abuse when the idea is interpreted to mean "like us", and there can be fine margins between what is acceptable and what isn't. If you have a strong affinity with someone, you're more likely to smile, laugh, make conversation and so on, and therefore are more likely to see them as "a fit" for the culture. It's ok to see if someone shares your company's values. But it might not be ok to prefer to hire someone who has more similar interests to you.

The good news is that being conscious of affinity bias can make a big difference. When we understand that working with people with different life experiences and different opinions is a good thing, we can strive to be open to surrounding ourselves with people regardless of these things, and begin to truly value that different experience and different point of view.

2 - Conformity Bias

When we try to fit in with the people around us rather than use our own judgement or contribute our own ideas, we have conformity bias. Humans like harmony, they like following the herd, and often see it as a virtue worth silencing ourselves for, for fear of disrupting the status quo. This psychological default probably dates back from our hunter/gatherer ancestors, where working together meant survival.

Take a quick look at this fascinating experiment by Derren Brown:

But conformity bias has all sorts of unwanted effects. Firstly, it halts innovation and creativity. If a dominant character wants to go with idea A, but someone else in the group who is generally less confident voicing their opinion in a group feels idea B is better, they may not say so. And if idea B really is better, that's a travesty.

Worse, that person might think that idea A is unethical, they might not say so for fear of rocking the boat.

When it comes to hiring, this can have immediate effects. If you're on a panel, and the two other panel members want to hire one person, you'd be more likely to agree, even if you have a good reason to think another person is better for the job.

3 - Attribution Bias

We're often predisposed to attribute the behaviour of others to something that is personal to them, rather than something that is part of their situational reality. Meanwhile, when we succeed, we're predisposed to attribute our success to ourselves, whilst when we fail, we're more likely to attribute our failure to external factors.

Unfortunately, attribution bias can lead us to think in a way that is biased against groups of people who are not like us, too.

For example, people are statistically more likely to think that women are less competent than men. Attribution bias means that we're likely to give women less credit for their accomplishments, yet blame them for more of their mistakes, where otherwise for a man we are more likely to blame external factors.

It's incredibly important that we consider all of these factors. We must give credit wherever credit is due, and particularly when assessing situations where things go wrong, we must consider both internal and external factors on an individual basis and with a view to improve and learn, not to blame.

4 - Dunning-Krueger Effect

...Or in other words, "The more you know, the less you think you know".

Self-confidence is a good thing, but only when it is synchronised with one's actual level of ability. The role of self-confidence isn't simply to project as high a level of ability as possible.

In his book Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders?, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic showed that, on average, women overestimate their abilities by 15%, but men overestimate their abilities by double that amount – 30%. The unfortunate result is that women's opinions are slightly more likely to be disregarded or overridden because of this tendency for men to be slightly more overconfident.

The effect can also cause people to say they believe something is true when in fact they are not sure. Meanwhile a contrary claim which is actually true suddenly faces opposition from a rogue untrue statement presented as truth. This leads to inaccuracy, confusion, wasting time and the wrong decisions being made.

This is also the effect we see when managers are predisposed to assume that something outside of their field of expertise is more straightforward than it is.

5 - Confirmation Bias

I read Prospect magazine. Prospect is considered by Media Bias Fact Check to have a slight lean to the centre-left. It's no coincidence, as I've always thought of myself as sitting around the centre-left on the political spectrum.

I have confirmation bias. I'm more likely to pursue and believe information which confirms things that I already believe to be true.

Another example? Ask a creationist and evolutionary biologist about the fossil record. The creationist says it's there to test our faith in God. The evolutionary biologist says it's proof of evolution.

This can also make us predisposed to engage with people who believe the same things we do. This isn't good, especially in the workplace. As we've seen above, we can be most productive and most ethical when we consider a range of opinions. What's the best practice here, then? We must try to be honest about what we do or do not know, and highlight when we are presenting something we believe is true rather than something that we know is true. We must also make an effort to recognise this in other people, and find considerate ways to watch out for this behaviour when it has a chance of adversely affecting another person or a project.

6 - "Beauty" Bias

Generally, the more attractive you think somebody is, the more likely you are to think they are competent. Conversely, this can be considered a kind of discrimination against those that a given group deem less attractive.

Did you know that, on average, CEOs are notably taller than people in other roles? In fact, they're NINE TIMES as likely to be taller than average..! Why? Well, tall people tend to be treated like leaders, and respond by acting more like one, even when growing up.

That said, here's an interesting thing – women that are generally considered to be very attractive are less likely to be hired, especially in senior positions. That's because beauty bias induces us to believe that very attractive women are less competent, which is obviously ridiculous given a moment's reflection.

Once we recognise this bias in ourselves, it's a relatively simple one to do something about. Be aware, and call ourselves out on it!

7 - The Halo Effect & The Horns Effect

These effects cause us to let one of somebody's traits overshadow their other traits. This could be either a good trait (halo) or a bad trait (horns). In other words, if you believe somebody has a negative trait, you're more likely to assume the worst about every aspect of them. Conversely, if you believe someone has a positive trait, you're likely to assume the best.

Let's say for example that there's somebody at work that really winds you up because of how disorganised they are. In a meeting, they suggest an idea. You automatically dislike the idea because that person is disorganised. This is clearly fallacious, and represents the Horns Effect in action.

Conversely, you're more likely to agree with somebody's idea if you have a good relationship with that person.

Really, every idea and trait should be taken in isolation, and weighed fairly. Avoiding making assumptions about people or their ideas can prevent our judgement getting clouded.

It's uncomfortable to know I'm biased, but it's something we all share.

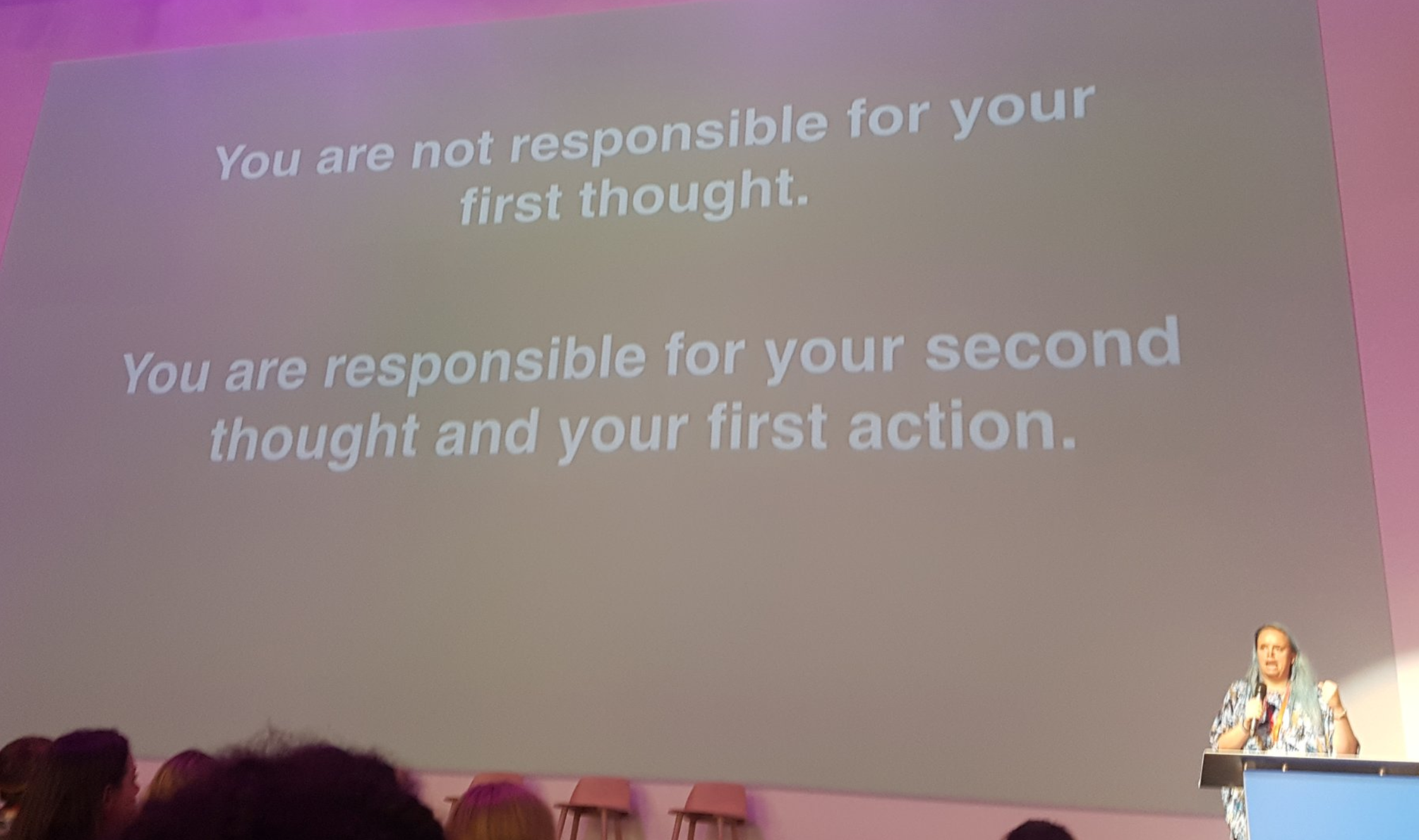

I'll leave this one with a photograph from Amy's talk, which is one of the best quotes I've ever seen and which I have carried with me each day since.